Katherine was born in an isolated section of an isolated state where creeks were called rivers and foothills called mountains, where the letter “r” held its rightful position in the word Washington.

She descended from generations that farmed winter-hardened soil, resisted Prussian kings, rebelled against Russian czars, and were lured to a land of flowing waters and fertile soil by handbills distributed via Santa Fe Railroad land agents who came to do good and did damn well. Katherine’s ancestors migrated through southern Europe, endured the Atlantic Ocean, forded untamed rivers, and found, not milk and honey, but homestead land with narrow streams and minimal access near a place they named Berdan America. They filed that name with the state, received approval from the railroad commission, then painted both names on the water tower.

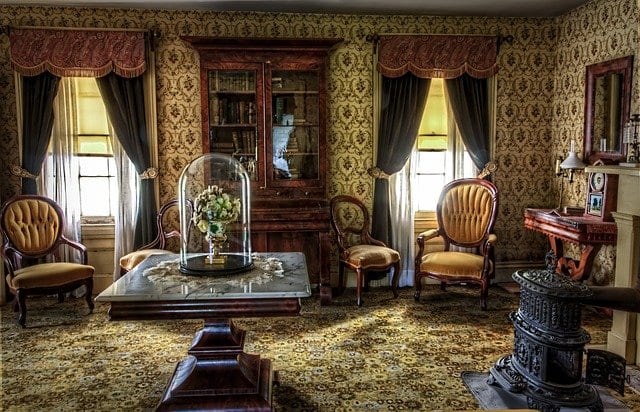

By 1884, her grandfather had built the house, the grocery store, and the lumberyard that her father inherited in 1916. Her mother died in the 1919 Spanish Flu Pandemic, and memories of the withered body inside a dark casket resting on a catafalque draped in black inside their small parlor still felt to Katherine, sixty-four years later, as if she had been locked inside the sepulcher on Good Friday.

After what seemed to be an eternity, her mother’s body was taken across the street to the limestone church. Burned beeswax candles, black vestments, dull chimes, and the cloying perfume of incense prolonged the dirge speed of the funeral mass. At the snow-covered graveside, the sound of dirt clods tossed by gravediggers onto the casket, followed by the whimpering of her brothers and sisters, coupled with her father, who lived for years as though he had been shot in the chest, continued to invade Katherine’s dreams.

When her father remarried, Katherine rebelled and migrated to her grandmother’s house where she was ingrained with the value of women, the value of learning, and the value of hard work.

Her formal education began in a well-built hexagonal building in front of the boy’s military academy next door to her family home where, at the age of seventy-two, she lived alone surrounded by large-print books and such ancient texts as Irving’s Sketch Book and a biography entitled Das Leben George Washingtons written in High German – each volume bore the imprint of Marian Catholic Girl’s school. On the inside of the book covers, written in a schoolgirl’s hand, were the names of her older sisters, Josephine and Mary.

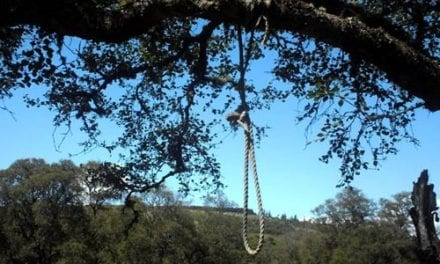

Over the years, Katherine built her life as if it were a vegetable garden surrounded by a protective moat. The only time a snake entered that garden was in the form of an untimely wartime marriage to a man she very quickly learned to dislike and avoid. Their four-year armed truce ended with his death, and resulted in her son, Gerald. She laughed seldom, smiled rarely, and acted as if life were designed solely for the execution of duty. But in her son’s presence, her eyes sparkled—nevertheless, she saw very early that her son walked too close to the barbed wire, and, each year she grew more determined to serve as his buffer to the world.

“Gerald will behave,” she told his grade school nuns, then added her trademark declaration, “If he doesn’t, you call me.” The few times they did call her, she dispensed the discipline learned from her grandmother – a mixture of love and German formation.

“At recess, they said I was fat,” Gerald blurted out one Friday evening when he was in the third grade. She spent the weekend instructing him how act assertively. When he told her of his fear, speaking in class, she enrolled him in elocution lessons.

As an adult, Gerald ate dinner with his mother every Sunday. On his way to her house one evening, there arose a memory from a time when there were only three entertainment centers in town – the football field, the church social hall, and the city auditorium. When Gerald earned his Eagle Scout award, he was asked to give the keynote speech at the ceremony that would draw over one hundred attendees into the city auditorium.

Gerald wrote the speech, his mother edited it, and for weeks, he rehearsed it with the elocution teacher and his mother. He inhaled the comfortable mustiness of the teacher’s basement where she conducted her after-school classes, and felt the crisp corners of the alcohol-scented mimeographed pages.

That evening, when Gerald heard his name called, he rose, adjusted his new Eagle Scout neckerchief slide, stood tall, and walked to the stage. As rehearsed, he placed the five-by-seven cards on the podium, looked at the audience, and spoke for over twenty minutes – seemingly without notes, seemingly at ease – so well-rehearsed that it appeared to be ad-libbed. He flourished on that lighted stage with the darkened hall in front of him – all of the audience seated, all of them waiting, most of them eager. It was that evening, when he lost all stage fright. The time when he was imprinted with preparation, rehearsal, and presentation.

His early high school grades were A’s and B’s. The B’s were not good enough. “Help me understand this,” his mother said and pointed to the only grade below an A. By “understand”, she meant the he should justify it to her.

During an out-of-state high school football game his senior year, Gerald caught a pass, ran fifteen yards, was tackled at the ankles, his body flipped one-hundred and eighty degrees, and with several bones cracked and protruding, he lay on the field. He watched his mother run toward him, and then drive him to the nearest hospital.

In the emergency room, she flashed her employee badge as the Nursing Director of the neighboring state’s largest acute care hospital, demanded the best orthopedic surgeon in the city, accompanied her son into the surgery suite, then watched over him afterward. He knew he was safe when, after he awoke, she walked toward him, and said, “Don’t worry; it will get easier. I love you”.

It was that day Gerald remembered, that moment when his mother stood between him and the world. He retreated to that memory often.

As Gerald turned the corner onto her street, his mind opened to memories of his mother’s chairs. At her home – floral, green, dark brown, beige, gray, finally peach. At work – cheap rolling chairs progressed to the high-back leather chairs. Gerald remembered how she rose from her chair, smiled and – erect and quick or bent and slow – gravitated toward him. He saw her old photos on the wall – Registered Nurse, young mother, nursing administrator. Her strong, assertive stance, generations ahead of her time. Her current photos, those of an old woman with eyes that saw in both worlds.

During dinner, Gerald noticed his mother had not taken her heart medications. “I forgot.” He took her weekly pill organizer from the counter, opened it. Inside the individual compartments, he saw five days of pills untouched.

Her house, overheated and desert dry, eyesight failing, frightened to navigate inside her own home, and unable to drive on her own, she sat stranded – reliant on visitors for food and sanitation.

“Nana,” he said to his mother as she sat slumped and unfocused, “I am moving in with you.”

As if she had forgotten the events of the day, she reached to touch their life years earlier, and said, “Just like before.” Added, “It’s sure changed.” She revealed a weakness never witnessed by Gerald when, with eyes that had declared love and protection, but now whispered weakness and passivity, his mother looked at him and said, “I’m so scared.”

One evening, Gerald found his mother on the floor near her peach chair. “Nana. Are you able to stand?”

She stirred and nodded yes.

“I’ll help you up.”

Her hands motionless, her unregistered eyes milky. He fed her soup, yogurt, soft buttered toast. She chewed for long minutes. She nodded when she finished, then forgot to chew the next small bite. A wave of nausea hit him.

Just the week before she had eaten caldo de pollo at a Mexican restaurant, and two weeks earlier she was the guest of honor at the annual family reunion. As the oldest surviving relative, whose youngest family members reminded her of long dead aunts and uncles, she presided at the head of the table. When the question was raised about the next gathering, she raised her head erect, scooted her chair back, and pointed to a group of young adults standing where, as children, they had stood only a few years earlier – young adults whose diapers she had changed, whose first communions she had attended – and said, “It’s their turn. Let their generation do it.”

Later that evening, as Gerald lifted his mother into her bed, she said in a barely audible voice, “This is hard work.”

Without thinking, he said, “It will get easier.”

Thirty minutes later, -911, emergency medical technicians rushed into the house, jerked his mother from her bed, laid her on the floor beneath her photos, cut her nightclothes, then applied the paddles.

Loud voices, then even louder voices repeated, “Clear.”

“She breathing; there’s a heartbeat.”

Followed by, “We lost it.”

The emergency medical techs applied electrical jolts to her chest. Gerald had observed his grandfather age, become disabled, and die during the twentieth century. He had long felt it was better to grow old in the twenty-first—it may have been, but, on that night, dying was dying.

He watched as her veins served as a foundation for needles and tubes. A paramedic yelled, “We got a pulse-”

Gerald leaned against the wall, and slipped to the floor. He began to perspire and breathe rapidly, felt his heart accelerate, attempted to catch his breath, stopped. Raised his head as if to speak, then realized it was a wasted effort. The right side of his jaw felt unaccountably sore – as if hit by a baseball bat.

He attempted to move his legs, tried to close his eyes and touch his nose, wanted to raise his right hand across midline of his head. This will pass. This will pass.

Within seconds, on the floor near his mother’s photos, “No heartbeat. Try again.”

Another technician, louder voice, “Clear.” Repeated. “Try again; no pulse, do it.”

Silence. “No heartbeat. Again. Heartbeat. None. Pulse. None.”

“Do it again. What? Repeat, please.”

Then silence. “Noted.”

Silence again.

Then, “Time of death…”

~~000~~

A veil of reddish brown-dust covered the cemetery entrance. Every sound entered the car—time and distance evaporated. One of the black-suited men said, “Slow down for the motorcycle.” The accelerator eased as the car coasted until the cyclist passed and waved them forward. They drove past manicured grass, trimmed trees, small structures near brick paths. Late arrivals acted as if they had run a gauntlet to get there, then stood frozen.

After a few minutes, Gerald was taken from the vehicle. Additional blasts of wind caused the men on both sides of him to sway. On this day, the wind was scented, not with robust pine resin, nor with delicate flowers, but with dust. Familiar people sang familiar hymns—there were the lingering odors of incense and the sounds of chimes. Light surfed from right to left as the sun moved above the canopy and highlighted two photographs on the table next to the priest.

A white-gloved man in the black suit spoke sotto voce, “You’ll need to move it a little to the left, then lower it just a bit,” after which the flat surface slid near the vertical tunnel just above the four by ten-foot opening, followed by the thud and echo of the casket as it struck the metal grave liner.

After the onlookers departed, and Gerald was alone, he heard a familiar voice, saw an iridescent image. Together, they relived walks in the vegetable garden, the magical appearance of bread and butter to make cucumber sandwiches. He felt warmth and protection. She leaned over, kissed his forehead, and said, “Thank you. I love you”, then placed a familiar hand on his shoulder.

“It’s sure changed.” He exhaled, then said, “This is hard work.”

“Don’t worry. It will get easier.” Then, “I love you.” It was the voice of his mother.