White Lies

Cassie tried to concentrate on the familiar scenery outside of the smudged, back seat window of her mother’s clunky black ’74 Impala. The same graying stalks of corn and the sagging wood of half-dead barns were flitting past as her mother flew down the winding country road. On either side, her five-year-old brother and two- year-old sister held fast to her hands. Mommy was raging at her from the front seat, but by now, at almost eleven years old, Cassie knew the argument was over when she stopped trying to make eye contact in the rear view mirror.

“Are you listening to me, Cassie?!”

“Yes, Ma’am,” she mumbled.

“What did you say?” came back from the front.

Mommy’s ranting died down and, with the exception of a few “dirty little liar” fragments, Cassie no longer heard anything she said. They slowed at the stop sign that separated the daily trip from the bus stop to the gravel road to their home. There was a white house on the corner—she liked to wonder about the people who lived there. Were they nice? Did they have children? She noticed the buck from their family of lawn ornament deer had been shot again. She hoped it was just a prank. Who would shoot at their own lawn deer?

At home, Cassie unbuckled her little sister from her car seat and cradled her in her arm while she gathered her book bag. Her brother didn’t help much with anything. He followed his mother as if he were the only child. Once she was sure she wouldn’t crush Becky’s fingers or limbs in the heavy black door, she slammed it shut. She set her sister down, hoisted her book bag onto her shoulder, and extended her pinky finger for Becky to grab. They walked the gray slate slabs to the front door together.

Once inside, Mommy barked at Cassie to put Becky in the playpen and then to go to her room.

“Don’t come out until I call you and you’d better have finished your homework by the time your father is home for dinner.”

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Cassie hadn’t always minded being sent to her room. In their old house, she’d had her own room, with blue carpeting and pretty lace-curtained windows overlooking a tree-lined street. Now she shared a brown room with dirty-looking beige carpeting—and walls covered with dark paneling—and no real windows. Just like the rest of the trailer. It was divided by a homemade bookshelf that held her brother’s toys. She stored her books under the bed.

Greeted by the cat waiting in the hall to follow her, she closed the door and flopped onto her bed. From her bag, she took inventory of the purchases she’d made at the school fund-raising bazaar. A red metal toy tractor for Rickie, $1.00; a soft little stuffed-animal kitten for Becky, $1.00; a seventy-five-cent metal measuring cup set for Mommy, who’d said you could never have too many when you were a good cook; and a wooden-handled pocket knife for her stepfather, Dave, $1.00. For herself, she’d gotten a National Geographic magazine from last February, 1980, for a quarter. Nothing else there interested her since they didn’t have any real books. The total should have come to $4.00, and the change she’d gotten was a quarter. She hadn’t looked at the receipt, hadn’t questioned the eighth-grader at the cash register. Cassie had assumed the older girl was right. Her mother thought differently. She accused her of using the other seventy-five cents to buy herself some candy at a store near the school.

Cassie defended herself, saying she’d done no such thing. “Always so precocious,” her mother said, “always trying to get away with things by blaming someone else.” Cassie insisted on her innocence as long as there was still hope of using logic. But it brought a full-on storm of accusations, nasty words and, for Cassie, complete disbelief that a cashier girl, whom she didn’t even know, could make this happen. Mother had railed about how selfish Cassie was, how much of a liar she was, and how piggish it was for her to buy herself candy instead of bringing home the change from the five dollars she’d been given.

Her mother’s Siamese cat rubbed its face against her leg and mewed. Cassie placed the items in a row on the lid of the white wooden toy box at the end of her bed—no one’s interested in them now—and pulled the cat up. She felt the rumbling of its purring and thought about her real father. She didn’t know him—he’d left when she was just a baby—but she had a picture of him she kept in a shoe box with her memories. “Why are you yelling at her, Peggy?” he would’ve said, “Stop it! “

Cassie kicked off her saddle shoes and changed from her plaid uniform and white blouse to jeans and a t-shirt. She’d finished her homework on the long bus ride. Crouching on the floor to find a book, she decided on her favorites: Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. She’d read them both several times now, but still loved the passages that made her cry. She’d look at the engraved illustrations and pretend she was either Jane—“Forgive me! I cannot endure it—let me be punished some other way! I shall be killed if…” Or Cathy, “Hush, my darling! I’ll stay. If he shot me so, I’d expire with a blessing on my lips.” Or both. She might be Jane now, but maybe, someday, she could be Cathy just for spite. She opened Jane Eyre to the inside cover and traced her maternal grandmother’s spidery cursive with her finger, “To Cassandra with Love on Her 10th Birthday – Grandmother.” She turned the book over and picked up Wuthering Heights. Flipping through the pages, she stopped at the picture of Cathy sitting on a stone wall, her hair billowing in the wind, wild eyes searching for Heathcliff.

Dave came home with a bang of the front door and the cat bolted. Now that they lived in a trailer, you could hear just about everything. She listened to be called to dinner.

“Sueeey! Suey, suey, sueeey!” Mommy got a kick out of calling Cassie to dinner with a pig call.

Cassie, sighed, closed the book, and slid both volumes back under the bed. She went back down the narrow, linoleum-tiled hall in her sock feet to the dining/living room. In the old house they’d had a separate dining room. Everything had been so much bigger. But Dave had lost his job and the house had followed. He was working again, though the pay was far less, Mommy said. He was always in a bad mood when he got home. Before they’d had to move from the pretty house on Hill Street, he’d yell sometimes—usually a short argument between him and Mommy that had nothing to do with children, and one that ended in laughter. Now their arguments were in long, low growls and always seemed to be about her.

She squeezed into her chair at the table; it was, as always, immovably wedged against the wall. It was Chinese food for dinner. Mommy loved making Chinese food and, in the old house, it meant a special occasion. An occasion, for inexplicable reasons, that called for candle light so the family could play a game about making up what kind of bugs were in the stir fry.

Plates were passed, grace was said, and the meal began under the dusty white pendant lamp, like any other dinner. Mommy asked Dave polite questions about his day. Rickie was prodded to talk about kindergarten. When the conversation dropped off, Mommy turned to Cassie, eyes narrowed and sharp. “Tell your father what you did today.” Her voice was too saccharine to be trusted.

“I bought everybody a gift at the bazaar and, instead of giving back all the change, I spent some of it on candy.”

Mommy’s jaw tightened. “What?” she hissed.

Cassie braced herself.

“You dirty little pig-faced liar,” Mommy said, her voice a low, measured tone from between clenched teeth.

“Did you lie to your mother?” Dave demanded.

“No. Yes. I mean…I don’t know!”

Cassie thought she was doing the noble thing by repeating her mother’s version of events. Becky started wailing in her highchair, and Rickie fiddled with the napkin in his lap.

“It has to be one or the other, young lady. Either you lied or you didn’t,” Dave shouted.

Cassie had no idea what to say and thought about it a little too long. Dave was sitting to her left and smacked her head hard enough to hit the wall behind her. Stunned, she blinked hard. Becky was red-faced and howling now. “What do you have to say for yourself, young lady?”

Screw you. Cassie wouldn’t have dared say those words out loud, even though she heard them at home all the time now. She stared down at her food and tried to imagine the varieties of gross things from the garden behind the house on Hill Street. There are grasshopper wings, weird white worms, these mushrooms could be snails. Definitely lots of maggots involved. She felt her mother staring at her and Dave quietly gearing up to give her another reason to answer more quickly. She lifted her chin and looked directly into his face. She was calm and confident when she spoke.

“I was given the wrong change for the stuff I bought at the bazaar today and Mommy didn’t believe that I hadn’t spent it. I didn’t spend it. I didn’t spend anything that I didn’t bring home. I don’t know why I got the wrong change. The girl who took the money was older than me so I thought I counted wrong. Mommy never believes me and I wanted to make her happy so I said what she said I did.”

Cassie’s mother’s mouth dropped open and her face blushed as she shot her a dark look. “Since when have you ever wanted to make me happy? You’re exactly like your father—you just make things up as you go along. You turn things around so you’re never guilty. You think you can always come up smelling like a rose.”

Cassie focused on the stir-fried maggots and pushed the wings and worms and snails around on her plate.

“A real pain in the ass, isn’t she?” Dave forced a laugh and cleared his throat.

“And she’ll end up with a really big ass, too, stealing money to buy sweets even when we feed her well enough, the little piggy,” Mommy said.

Rickie giggled at the words “little piggy,” and Becky stopped crying because Rickie was laughing. Cassie kept looking at her tainted food. Mommy and Dave went back to talking about his job and how stupid his boss was.

Cassie thought about the picture of her father. She’d stolen it from her mother’s old photo album. He was sitting by a swimming pool laughing, a cigarette in one hand, a beer can in the other. The photograph was dated ’71—ten years ago—but what month? Mommy said he went to Mardi Gras and never came back. But Mardi Gras would have only been during a February. She had read that in The National Geographic. Which February?

“May I be excused, Ma’am?”

“Not until you’ve finished everything on your plate, Miss Piggy,” said Mommy, smiling at Rickie.

Cassie sat there, concentrating on her plate, trying to re-imagine it. Rice…snow peas…bamboo shoots…water chestnuts…mushrooms…I like all those things. This is silly. But she couldn’t manage to do anything but push the food around on her plate. She couldn’t erase the fictitious mess in front of her. When everyone else had finished eating, Mommy ordered her to leave her plate but clear the rest of the table, put Becky to bed, and wash the dishes. She and Dave lounged on the overstuffed couch and laughed at an old comedy on television. A couple of times Mommy ordered “Miss Piggy” to bring them a couple of beers.

It wasn’t pleasant washing the dishes. Leaning her forearms against the edge of the sink, her mind wandered, and she imagined her father as an invisible witness. He would shake his head with disapproval. He would take her face in his hands and tell her that it was okay that she looked like him. That he got lost on the way back from Mardi Gras but was coming back to get her soon. “Be strong,” he would say.

Dishes done, she dried her hands and asked for permission to go to her room even though her dinner still sat on the table. Her mother dismissed her drowsily—she couldn’t drink more than one beer without falling asleep. But Dave said he had one more chore for her.

“We’ll take out the trash together. Gather it up in the kitchen and I’ll be right there.”

Cassie knocked the kitchen sink’s drain-catch into the garbage. Dave came in with her plate and scraped it into the bag without a word. He tied it up and pulled it from the can. She washed the plate, shook off the water, and put it away.

“I know all of this is tough for you,” he said in a near whisper. “I’d really like to see what you got for everyone today. I know you weren’t lying. When you said that you didn’t spend the missing money on candy, I knew you didn’t. Let’s take out the trash. I want to show you something. Go get your coat.”

Dave was sometimes nice after Mommy passed out. Cassie slipped past her mother and down the hall. There was a light snore coming from her brother’s side of the room as she pulled on a jacket, slipped her sneakers on, and swept the gifts into her book-bag to bring with her.

In the kitchen, Dave had his coat on and the garbage bag in his hand. “Let’s go,” he said with a smile.

She followed him through the back porch that was the beginning of a house they were planning to build to replace the trailer—someday. Dave dropped the bag into the metal can, clapped the lid back on and motioned for her to come around the house and up the flagstones to his pickup truck.

“I just want you to know that you don’t need to stay in your room all the time with the books you keep under your bed and the damned cat. I know it’s tough for you. Your mother and I don’t make it any easier. Shit, I was your age once. Nothing like you, but your age at least.”

He leaned against the truck and pulled out a pack of cigarettes from an inside pocket. He lit one and inhaled. She didn’t know that he smoked, and she doubted her mother knew either.

“You’ve got to get out and let off steam sometimes,” he exhaled. “You know what I do?” He didn’t wait for an answer. “I go hunting.” Dave made air quotes when he said the word hunting and grinned. “Don’t you ever tell your mother; she’d kill me.”

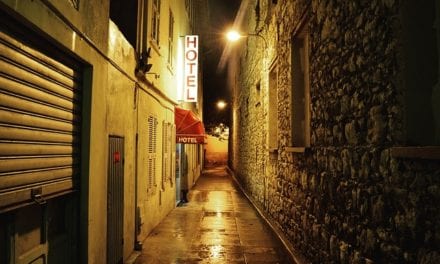

He opened the passenger door for her to get in. Cassie pushed her purple backpack onto the floor and climbed up onto the seat, slamming the door behind her. Dave flicked the cigarette across the road, its red tip bouncing into the darkness. He drove in silence to the intersection at the end of their gravel road, stopping on the shoulder across from the white house on the corner—the one she passed on the way home from school every day. Its broken windows stared blankly at the lawn. She looked at Dave’s face, lit up by the green of the dashboard light. The gold of his wedding band on the top of the steering wheel was caught by the headlights.

Gold. That’s one of the colors of Mardi Gras.

“Don’t worry,” he said, “that house has been empty for years.” Dave got out of the cab and pulled the rifle from behind the seat. Cassie remembered that he kept it behind the seat of his battered truck so it wouldn’t be in the house—a safety measure, he’d said. He lifted it to his shoulder and took aim. The blast echoed as an antler on the plastic buck shattered. Cassie tucked her hands under her legs on the cold pleather seat and held her breath.